Up until recently, I wouldn’t have considered using the phrase “Celtic erasure.” Certainly, growing up in Chicago, “Celtic” was everywhere. St. Patrick’s Day—at least the Chicago-several-generations-removed-from-Ireland version—was characterized by green beer, the Chicago River being dyed green, and people dressing in green. It was everywhere. People of Irish descent with the last name of “Daley” occupied the Chicago mayor’s office for all but thirteen years between 1955 and 2011. Another member of the Daley family served as a cabinet member in the Clinton Administration and chief of staff in the Obama Administration. No Celtic erasure there, it seems.

But these modern phenomena say little about concerted efforts to wipe Celtic languages and cultures off the map in Britain and Ireland prior to the 20th century. Efforts to deny the existence of Celtic cultures exist even today. And I’ve begun to understand how cultural appropriation in parts of the modern Pagan movement unwittingly contributes to the continued erasure of Celtic culture.

If you read nothing else in this article, read this: Pagans don’t have to stop celebrating Samhain, Imbolc, Beltane, or Lughnasadh. There are other ways to put a stop to this cultural erasure. We need only understand the origin of the celebrations, acknowledge their origin when we celebrate them, and respect the cultural context of them as much as possible. Unfortunately, this acknowledgment does not occur nearly as much as it should, and this contributes to Celtic erasure.

Some clarity on my position and Pagan practice

Before I comment further about Celtic erasure, I want to talk a little bit about my approach to Pagan practices originating in what are often referred to as the “Celtic countries.”. This will hopefully help you put what I say into context. When I had my Pagan reawakening and felt called to explore what likely were the pagan practices of at least some of my Scottish and Irish ancestors, I came across the Celtic Reconstructionist website Paganachd. They talked about how Celtic Reconstructionism came into being in the 1980s. A number of Celtic practitioners were dissatisfied with the popular approaches to Celtic spirituality at that time. They started to collaborate and try to piece together a Celtic spirituality more in line with actual historic practices, as opposed to the eclecticism that changed native practices in Ireland and Britain into something very different from before.

I also want to clarify a few positions I hold in regards to Paganism and cultural appropriation:

First, I support the efforts of indigenous peoples to protect their religious traditions from cultural appropriation. Cultural appropriation changes and can sometimes ruin indigenous practices when people with more money and connections, more power, and more access to the media adopt and publicize these practices out of context of the original culture. Practitioners of these closed religions are often trying to protect a tradition they often had to keep hidden and in secret as their religions became illegal. They have the right to insist on such protection. This is because it becomes hard to preserve one’s own tradition when people outside of the tradition are defining it for you. In some cases, such as the situation with white sage, people actually risk losing access the resources critical for continuing the tradition.

Second, even the use of the word “Celtic” is problematic in and of itself as it erases the distinction between Irish, Scottish, Welsh, Manx, Cornish, and Breton cultures. However I use the term in this article because it’s a widely used term and I want to catch the attention of people who use this term to think about the histories of what are often referred to as the “Celtic nations,” and their implications for Pagan practice today.

I believe that many of the traditional indigenous practices of Ireland and Britain and many of their holidays are open to anyone who feels called to them. People need not live in or have heritage or ancestry from the six counties often labeled as Celtic countries in order to practice it. Your nationality, ethnicity, (and especially the color of your skin!) does NOT determine the degree to which you will treat a tradition with respect. But in doing so, you need to understand the culture on its own terms, understand the history of colonization and oppression.

I am vehemently opposed to the appropriation of these indigenous practices or “Celtic symbols” as part of a white supremacy agenda. Some white supremacists fetishize these cultures. I consider that to be appropriation and actually part of the phenomenon of Celtic erasure. A look at Celtic history would make it clear that establishing any sort of ideology putting down other cultures or establishing the supremacy of one culture over others is antithetical and indeed a slap in the face to generations of people from Ireland and Britain.

I am not here to declare what is correct or incorrect Pagan practice. I also don’t speak for all Pagans , much less people practice traditions, I am an American removed from my Scottish and Irish heritages by at least eight generations. While I have conversed online with Scottish and Irish practitioners, I don’t consider it appropriate to call myself Scottish or Irish. Other Americans should show the same regard for their countries of ancestral origin.

I am but one Pagan practitioner influenced by his ancestry giving my opinion on respectful treatment of these traditions. I put forward these arguments to be considered on nothing but their own merits. I claim no authority on these religions beyond that.

Finally, I recognize that some people may object to my use of the phrase “Celtic erasure” as extreme. But it was explicit policy at various times in Britain and Ireland. And I use the same phrase to describe the effect that cultural appropriation has on these cultures today. A key element of cultural erasure–and often one of its final acts–is acting as if the culture never existed in the first place. In these cases, deliberate malice and intent to destroy the culture is no longer necessary for cultural erasure to occur. Below, you will see concrete examples of how this happens.

Know your history

I firmly believe that anyone wishing to celebrate Imbolc, Beltane, Lughnasadh, Mabon, and Samhain needs to be mindful of Celtic history and the efforts at Celtic erasure, particularly in the British Isles and Ireland.

What are now considered to be the Celtic countries across Britain, Ireland, and northern France are merely the last vestiges of a decentralized Celtic world that once extended through France, central Europe, and as far east as Turkey, at a time when the notion of nation-states did not really exist. The Symbolsage website documents some of the evidence of Celtic Fire Holidays being celebrated in other parts of Europe

Celtic languages, both living and extinct, are a branch of the Indo-European language group. Scholars have divided the language group into the Insular group of languages found mostly in the Britain and Ireland, and the Continental group of languages across continental Europe. Scholars sub-divide the Insular Celtic languages in Britain and Ireland into the Goidelic (Gaelic) languages spoken in Ireland, Western Scotland, and the Isle of Man, and the Brythonic (often referred to as Brittonic) languages spoken throughout the rest of Britain.

The Continental Celtic tribes declined in large part due to Roman conquest. All the languages from that language branch are reported to be extinct. (Though significant remnants of Continental Celtic culture can arguably be found in the Galicia region of Spain.) The Roman Empire expanded into Britain and southern Britain was largely Romanized. Nevertheless, Celtic languages were still very widespread and often dominant in southern Britain for centuries afterwards.

Anglo-Saxon settlers started arriving in what is now England in the fifth and sixth centuries CE. They brought with them a West Germanic dialect that became known as Old English. A western push of Anglo-Saxon settlers and culture marginalized the Gaelic-and Brythonic-speaking peoples to such an extent that by the end of the first millennium CE, Brythonic Celtic languages only remained in what is now known as Wales, Cornwall, and a settlement in the northwest part of what is now France known as Brittany.

But Celtic languages were still very present in Britain and Ireland well into the second millennium CE. The decline and near-disappearance of the Goidelic and Brythonic Celtic languages in Britain and Ireland is due to the efforts of England asserting its political, cultural, and economic dominance over these countries.

This effort rarely resulted in actual policies explicitly designed to wipe out these languages, but such explicit policies did exist. The establishment of English as the sole official language meant that it was necessary to speak English to get ahead. It also put English speakers in a higher class than non-English speakers. More explicit efforts to wipe out Celtic languages were implemented frequently in the 19th century. This was done by educational institutions zealously making efforts to “civilize” Gaelic speakers from their native tongues. And in the 18th and 19th centuries, a combination of economic exploitation, forced removals, and famine accelerated the decline of indigenous language and culture in Scotland and Ireland. As is true in other countries, when there is economic dislocation, it often falls hardest on the minority culture., and this is often by design. Whether implicit or explicit, Celtic erasure was British policy for several hundred years.

Establishing English supremacy in Wales

King Edward I of England conquered Wales in 1283. He appointed his heir to the post of the Prince of Wales. With the exception of about fifteen years during a Welsh rebellion against the English at the beginning of the 15th century, the person next in line to the English throne (which is now that of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) has held that post. King Charles III held that post until his recent coronation, and it is now held by his son, Prince William.

The name “Wales” is actually an Anglo-Saxon word meaning “foreigners.” This is ironic given that the Welsh language is reportedly the oldest currently existing language in Britain. The Welsh have historically referred to the name of their country as Cymru, and the language Cymraeg. The act of declaring natives as “foreigners” is a theme that has repeated itself in other former British colonies. Especially in the United States.

But the Cymraeg language thrived in Wales despite the 13th century conquest by the English. This began to change somewhat in the 1530s and 1540’s when England, under King Henry VIII, formally declared Wales to be part of England. A series of laws made English the sole official language in Wales and required in government.

But this also happened around the same time of the establishment of the Church of England (which was Protestant). The Protestant Reformation and all the controversies around it were raging across Europe. Ironically, the British crown’s”s zeal to establish Protestantism in England helped preserve the Cymraeg language for several centuries. The Crown and the Church decided that printing Bibles in Welsh would promote religious unity. So under orders from the Crown in 1566, every church parish was given a Welsh translation of the Bible. As a result, Cymraeg remained dominant as the language of the community and church in Wales, at least for a few more centuries.

The Industrial Revolution and immigration of English people into Wales and mass-produced English books during the 19th century accelerated the decline of Cymraeg as a language. In urban areas, English began to be heard in the workplaces, pubs and on the street. This provided more incentives for people to learn English.

More ominously, the Industrial Revolution implemented compulsory education, and organizations. The National Society for Promoting Religious Education forbade the speaking of Welsh by schoolchildren on school grounds. One notorious tool widely use was the Welsh Not. This was a stick used which would be used to inflict corporal punishment on children to discourage them from speaking their native tongues.

Martin Johnes, Professor of History at Swansea University said that at the beginning of the 19th century, about 80% of the people in Wales spoke Cymraeg and few could speak English. By the 1891 census, only 50% spoke Cymraeg, and in the 2011 census, it was down to 19%. Mass media and consumer culture are considered the main reasons for the decline of the Welsh language in the 20th century.

Starting in 1997, the United Kingdom began the process of devolution. This allowed for the provision of local parliaments in Scotland and Wales. Since then, the government of Wales has begun to promote the Cymraeg language. They have an initiative called Cymraeg 2050 that has set a goal of one million Welsh speakers by 2050. BBC Cymru Wales has existed since 1964, and has been broadcasting a growing number of programs in Cymraeg.

Establishing English supremacy in Scotland

In Scotland, the history of Celtic languages is more complex. This is because Scotland arguably has a a longer history of being a multi-cultural country.

Gaelic was widely spoken throughout Scotland in the first millennium CE. Its greatest concentration of speakers were in the north and west of the country. This was particularly true in the kingdom of Dál Riata, which existed between the fifth and ninth centuries CE. This kingdom straddled the North Channel between the Irish Sea and the Atlantic Ocean and also included parts of Northern Ireland.

But Gaelic speakers weren’t the only ones living in what would become known as Scotland. It needs to be made absolutely clear that Scotland was never, ever, an exclusively Gaelic country. The Picts were located to the north and the east of the country. They reportedly spoke a form of Brythonic Celtic. What we now know as Scottish Gaelic spread throughout most of what is now Scotland when Dál Riata and the Pictish kingdoms merged in the 9th century to become the Kingdom of Alba, which later became known as the Kingdom of Scotland. But Gaelic was never widely spoken in what is now southeastern Scotland.

Many historians mark the start of the decline of the Scottish Gaelic language at the end of the 11th century CE. At that time, Malcolm III (Malcolm Canmore), the King of Scots, married Princess Margaret of Wessex, a member of the English royal family prior to the Norman conquest. Margaret encouraged English settlement in Scotland and gave her children Anglo-Saxon names. Both the King and Queen died in 1093, and Gaelic-speaking nobles pushed aside the English-speaking heirs. They installed Donald III (known as Donald the Fair) as the King of Scots. They also made an effort to drive out the English who had been with King Malcolm. But the sons of Malcolm III regained the throne of the King of Scots with help from an Anglo-Norman army in 1097. In subsequent centuries, Anglo-Norman names began to spread through the region, particularly in the Scottish Lowlands. By the 1300s, Gaelic was widely replaced in the Lowlands by what is now known as Scots, a Scottish dialect related to English. Gaelic completely disappeared from the Lowlands by the 18th century but remained dominant in the Highlands.

There was a point where Lowlanders began viewing themselves as culturally distinct from the Gaels, I haven’t done enough research to figure how this practice began. But they began to refer to their West Germanic-related dialect as “Scots”. They also began to refer to the Highlanders as “Erse” or Irish, making the language of the founders of Scotland out to be a foreign language. (See how native people are again made to be seen as foreigners?) Furthermore, the rise of Protestantism in Scotland moved more slowly in the Highlands than the Lowlands, and so prejudice against the Gaelic-speaking Highlanders was accelerated by religious conflict. Both of these developments accelerated Celtic erasure.

A series of laws by King James VI of Scotland (James I of England) in the first half of the 17th century sought to unify Scotland by requiring all of the landed gentry to speak English. But Scottish Gaelic persisted among the people in the Highlands. King James considered Gaelic to be among the chief impediments to Scottish unity. He also saw it as an impediment to “civilization.” which in this case also included literacy and Protestantism. The policy of Celtic erasure was becoming more explicit.

The Acts of Union in 1707 made Scotland part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain. Around this time, the Society in Scotland for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SSPCK) established schools in Gaelic-speaking parts of Scotland, as did the Church of Scotland. These schools were English-only. They even banned the speaking of Gaelic by schoolchildren. Some later partially retracted that policy, considering Gaelic s a stepping stone for teaching English. Nevertheless, Celtic erasure was, at this point, explicit social policy.

The Highland Clearances, spanning from roughly 1750-1850, is referred to in Scottish Gaelic as “Fuadaichean nan Gàidheal”, translating to “the eviction of the Gaels.” Some historians view the clearances as, in part, revenge on the Highlanders for the Jacobite uprisings, though there is no consensus regarding that. “Crofters” were tenant farmers who had lived on the land—and sometimes in the same houses—for multiple generations spanning hundreds of years. They often lived near other members of the same clan. But landowners owned vast tracts of the land these crofters lived on. Starting around 1750, they determined that they could make more money grazing sheep than collecting rents from crofters. So they began to evict crofters en masse from the land. Sometimes they went as far as to burn down their houses in order to force them out. Entire villages were cleared of residents, sometimes with entire towns set on fire. Some Highlanders froze or starved to death, some were able to move to the coasts, but many emigrated to England, North America, and Australia. Landowners often subsidized emigration to other countries, deeming it a small price to pay to get rid of their poor. The Scotsman newspaper at the time condoned this activity. They referred to it as “the removal of a diseased and damaged part of our population.”

The Scottish government, in existence since the 1997 devolution, has made commitments to promote Scottish Gaelic as well as Scots. Even the BBC has gotten involved.

Establishment of English supremacy in Ireland

In Ireland, the decline in Gaelic language began with the Tudor conquest of Ireland in the 16th and 17th centuries. Across Ireland, wealthy English and Scottish people bought up land and divided the country into plantations, with the native Irish renting from them. There was explicit Celtic erasure talk even at that time. One writer said, “We may conceive and hope that the next generation will in tongue, and in heart, and in every way else, become English; so that there shall be no different or distinction, but the Irish sea betwixt us”

But the numerical decline of Gaelic speakers didn’t really take hold until after the Act of Union of 1801 created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Starting in 1831, the school system banned the use of the Irish language (Irish Gaelic) in the schools. One manifestation of this was the use of a “tally stick”, very similar to the Welsh Not. Each time a child was caught speaking their mother tongue in school, a notch would be carved in the stick. At the end of the day, they were physically punished based on the number of notches. Talk of Celtic erasure was now being backed by explicit policy.

Another major factor in this was the Great Irish Famine which began in the 1840s. While the British government set up (often ineffective and sometimes counterproductive) efforts to aid the Irish in 1845 and ‘46, the British government withdrew the aid by ‘47. The Whig government in Britain considered it a “moral hazard.” The burden of offering the aid was shifted from the British government to local taxation. Yet the British government refused to bar the export of food from Ireland . This meant that resources that could have been used to alleviate the famine was instead exported by the wealthy landowners. Many Irish were packed into overcrowded workhouses, which further fed the spread of disease among already vulnerable populations. Over 200,000 Irish people perished in the workhouses alone. In addition, over half a million people were evicted and left homeless. Those with the means to leave did. In the end, over a million people died and 1.25 million people emigrated.

The famine kicked off a century-long decline in population that Ireland (both Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland combined), even as of 2023, hasn’t fully recovered from. In 1841 the population of all of Ireland was estimated at 8.18 million. Just ten years later it dropped to 6.55 million, a precipitous drop of nearly 20%, due to death from the famine and emigration. It continued to drop over the decades due to better economic opportunities elsewhere. It reached a low of 4.21 million in 1931. This diaspora resulted in Irish communities being scattered around the world.

The Republic of Ireland, since its founding, has recognized the Irish language as an official language of the country. (“Irish” is the proper English term for Irish Gaelic. Even the Scottish Gaelic language refers to the Irish Gaelic language as “Irish” without adding the word “Gaelic”) Various efforts have been made to revive the language.

Modern “alternative history” promoting Celtic erasure

Recently, there have been efforts to try to deny certain aspects of Celtic history in Britain. Some have argued that the Celts were never in Britain to begin with. They, base this on lack of evidence about this in ancient writings of the time. Cambridge professor Susan Oosthuizen put forward a claim that Anglo-Saxons never invaded or colonized Britain.

Such assertions ignore linguistic similarities between the Celtic languages in Britain and on the Continent. They also ignore the linguistic similarities between Old English and other West Germanic languages. There is also evidence of similar rituals and deities in both Britain and the Celtic areas of Europe..

Even more disturbingly, the University of Cambridge’s Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Celtic (ASNC) has taken an official position denying the existence of English, Scottish, Welsh or Irish people as separate peoples with distinct cultural identities. This is being presented as an “anti-racist” effort. In reality, it is very blatant Celtic erasure. Would the 19th century children in Wales, Scotland, and Ireland being prevented from and sometimes being beaten for using their native language in school agree with such claims?

I think most anti-racism activists would view the university’s appropriation of the term “anti-racism” as extremely cynical. It’s like saying that anti-racism in the USA requires denying the existence of Black, Latino, and Indigenous people. It’s impossible to be anti-racist and at the same time deny the existence of multiple cultures. Cambridge University’s statement also clearly fits the agenda of defusing British devolution and dismissing ethnic minorities’ claims to the right of sovereignty. That an elite British educational institution would take this position isn’t the least bit surprising.

Really, it’s a verbal sleight of hand. Ethnic groups don’t have to go back 3,000 years to be valid. It is true that many if not all of these ethnic groups have had subgroups, as I have already demonstrated with Scotland. This is also true of the Indigenous and Black cultures within the United States. Denying the fact that a group people exist is often part and parcel of other efforts to deny that group agency, sovereignty, and the right to determine their own destiny.

It should be noted that in a speech immediately prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Vladimir Putin gave a long speech that insisted that Ukraine was in fact a creation of Vladimir Lenin, rather than a distinct culture and language going back centuries. Israeli prime minister Golda Meir said, “There was no such thing as Palestinians…It was not as though there was a Palestinian people in Palestine considering itself as a Palestinian people and we came and threw them out and took their country from them. They did not exist.” Just recently a far-right Israeli minister claimed that there was “no such thing as a Palestinian people.” just weeks after he called for the Palestinian town of Huwara to be “erased.”

Certainly, talk of Scottish independence, Welsh independence and Irish reunification is causing consternation among the elites in the United Kingdom. Cambridge University and the authors of the articles denying the Celtic presence in the UK and extensive Anglo-Saxon colonization of Britain might not explicitly state their political biases. But certainly, these academics do support a narrative that seeks to slow or perhaps even reverse devolution in the UK.

“Celebrated in the English-speaking world for thousands of years”

Now that I’ve shown older and modern efforts of erasing Celtic cultures from the map, I want to focus on how Pagans have unwittingly contributed to Celtic erasure.

My eyeballs popped out of my head when I came across this TikTok video late last year. This American author adamantly denies that “everything within Wicca is cultural appropriation.” But then he proceeds to completely shoot himself in the foot. He demonstrates precisely how a number of Wiccans, including himself, have actually engaged in serious cultural appropriation.

He begins his argument by suggesting that those accusing Wicca of cultural appropriation are actually appropriating Wicca themselves. “There are people who just hate Wicca anyways, for whatever reason, often while practicing something that looks a lot like Wicca.” He makes himself look rather silly reversing the accusation. Does he genuinely believe the organizers of the big Beltane and Samhuinn Festivals in Edinburgh are stealing from those poor Wiccans? Indeed, how can Samhain be just a Wiccan celebration when Samhain is also the month of November in both the Irish language and Scottish Gaelic. The old spelling of Lughnsadh is spelled “Lúnasa” in the modern Irish language and Lùnastal in Scottish Gaelic, and both are also the names for August in their respective languages. It must be noted that the four fire holidays celebrated in Irish and Scottish practice were largely local celebrations which in some cases had names changed by the Catholic Church. Celebrants of these holidays didn’t consider themselves Wiccan, much less Pagan.

Nevertheless, this American author said that the notion of the sabbats being cultural appropriation was “quite laughable,” while at the same time demonstrating precisely how Wicca engages in cultural appropriation. He said, “six of the eight sabbats have been celebrated in the English-speaking world (sic!) for over a thousand years.”

English. Really? Does he know the history of England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland? (As someone who is also American, I can testify that most of us are not really taught much in the way of this history). Do most English speakers even know how to pronounce Lughnasadh? I’ve literally witnessed American Pagans confidently declare that the word is pronounced “Lammas” which is actually a distinct English holiday also celebrated by some Pagans and Christians.

He finishes his argument by employing a “we are one” argument often used by people defending cultural appropriation. He said “Wicca is part of the Western magical tradition” that goes back thousands of years.” He said that it was practiced by the ancient Romans, Egyptians, and Babylonians, and then later on picked up by Jews, Christians, and Muslims, and was part of “every society that I can think of.” I think practitioners of many of these religions would be surprised to be told that they are practicing “Western magical traditions.”

So in a comment on his video, I posted a question asking him which six of the eight sabbats were “part of the English-speaking world for thousands of years.” He replied, “That’s easy,” and then went on to list Yule, Ostara, Imbolc, Beltane, Lughnasadh/Lammas (he put the two together as one holiday) and Samhain. I pointed out to him that four of those six (really seven) holidays he listed were in fact not English in origin, but Celtic, and he had no right to call them “English.” He ignored me.

He also didn’t mention Mabon, which was invented by a California Wiccan in the 1970s. That author wrote, “It offended my aesthetic sensibilities that there seemed to be no Pagan names for the summer solstice or the fall equinox equivalent to Ostara or Beltane—so I decided to supply them.” He named the autumnal equinox Mabon after a Welsh deity. But Welsh Pagans had not previously named a holiday after Mabon, nor had they been consulted when the Californian decided to “supply” this Welsh deity name. I’m aware that there are Welsh Pagan practitioners who would be more than happy to tell this California Wiccan where he can put his “aesthetic sensibilities.”

Wicca is a valid religion. Wicca originated in England. The religion was essentially the first Pagan organization out-of-the-broom-closet in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. Many of its leaders back then gave themselves wide latitude in setting the parameters of the growing Pagan movement. Being part of the majority culture in Britain, their values were a reflection of the values of the dominant society, and as such, they engaged in cultural appropriation.

There’s no reason to, as the Llewellyn author put it, “hate Wicca.” Furthermore, Wicca today cannot be said to have a central authority. They have no means of enforcing norms of practice. Many Wiccans do in fact make efforts to avoid cultural appropriation and provide appropriate respect for non-English cultures. More Wiccans need to do so. It is incumbent on Wiccans today to correct the distortions of their 20th century founders. They need to give Celtic culture and practices the respect that they deserve.

As I said in the beginning of this article, this means acknowledging the true origins of Imbolc, Beltane, Lughnasadh, and Samhain, when celebrating these holidays and respecting the cultural context of them as much as possible when celebrating these holidays. And yeah, it would be really nice if they didn’t refer to the Autumnal Equinox as Mabon.

I am going to share a tangible example of what happens to a cultural practice when people outside the culture with more power and influence take it upon themselves to define the cultural practice for the public.

A Duck Duck Go search and its interesting results

During the week before Bealtaine this year, I was thinking about what I’d do for a Bealtaine ritual I was planning. I decided to check to see if there were specific deities associated with Bealtaine in the same way Brigid is associated with Imbolc and Lugh is associated with Lughnasadh. I have deities I already work most closely with and I wasn’t likely to work with any others for Beltane. But I was nevertheless curious.

It must be noted that at that time, I didn’t known that the proper spelling for the May fire holiday was “Bealtaine,” pronounced “Be-AL-ten-uh”, and like most people thought it was “Beltane” or “BELL-tain.” I ran a search on the Duck Duck Go search engine using the keywords, “deities associated with Beltane”. To be honest, I was floored by the recommendations that I found in many of the listings.

Neither the culture nor the lands from which Beltane came from was listed in four out of the first five listings of this Duck Duck Go search. Only five out of ten said anything about the true origins of the holiday, Seven out of ten listed non-Irish deities prominently. Five out of ten of the websites even listed deities from indigenous religions from Africa and the Americas. I have little doubt that practitioners of those non-European religions would have something to say about their deities being added to a European celebration without their consultation.

Here are the top ten listings from that Duck Duck Go search. I summarize below what they said and didn’t say about the origin of the celebration. I also list the deities they listed, in order of being listed. References to non-Celtic deities I put in italics.

LearnReligions.com provided a listing of twelve, yes, twelve “fertility deities” associated with Beltane. They listed eight Greek or Roman deities, two Celtic deities, and one Egyptian, one Hopi, one Zulu, and one Aztec deity. There was no mention of Beltane being originally a Celtic holiday.

EclecticWitchcraft.com was, happily, not too eclectic with their menu of Beltane deities. They selected only Irish deities for their list and identified them as Celtic.

Exemplore.com confidently listed Aphrodite/Venus (Greek/Roman), Freya (Norse) and Flora (Roman) as the goddesses most associated with Beltane. Pan and Dionysus (both Greek), were the first gods mentioned for Bealtaine. Exemplore mentioned the deities Cernunnos and Bel next. who are sometimes considered “Celtic” deities. They followed this with Sol (Norse), and finally, they said that “Ra, Egyptian God of the Sun, is also appropriate. They also reference Beltane as a “special stop on the Wiccan Wheel of the Year,” but did not mention the the lands from which the Beltane celebration originated.

Witchesofthecraft.com said “Some Beltane Goddesses to mention by name here include Aphrodite, Arianrhod, Artemis, Astarte, Venus, Diana, Ariel, Var, Skadi, “Shiela-na-gig” (yes, it’s misspelled), Cybele, Xochiquetzal, Freya, and Rhiannon. Beltane Gods include Apollo, Bacchus, Bel/Belanos, Cernunnos, Pan, Herne, Faunus, Cupid/Eros, Odin, Orion, Frey, Robin Goodfellow, Puck, and The Great Horned God.” There was no mention of Bealtaine originally being an Irish holiday or talk about the lands where the holiday came from.

Witchesofthecraft.com also occupied the fifth spot on the list, but this time copied LearnReligions.com’s “12 Fertility Deities” list. This also means that there was no mention of Beltane originally being a Celtic holiday.

TheWholesomeWitch.com listed four Greek deities and three Celtic deities. Aphrodite, Artemis, and Brigid were listed as the Beltane goddesses. Bel, Cernunnos, Eros, Pan were listed the Beltane gods. But the website did describe Beltane as a “long standing Celtic holiday.”

SymbolSage.com listed only the Celtic deity alternately listed as Bel, Beli, or Belenos. They actually only used the word “Celtic” once, but they did reference the geographical origins of Bealtaine. They also provided purported evidence of Beltane being celebrated on the European continent, particularly Beli in Italy, Spain, France, and Denmark as well as the British Isles. They didn’t connect the dots to point out that these were areas that were once home to Celtic peoples. But they did a good job describing the holiday and describing both Welsh and Scottish celebrations of the holiday.

LightWarriorsLegion.com listed Artemis, Cernunnos, Flora, Xochiquetzal (Aztec), and Bel. They added, “other deities include Oya (Yoruba), Mbaba Mwana Waresa (Zulu), Pan and Hera (Greek), Apollo, Freya, Odin, Venus, and Diana.” They did at least refer to Beltane as a Celtic holiday.

OutdoorApothecary.com did talk about Bealtaine being a Celtic holiday. But they did not mention any deities other than the “God” and “Goddess,” which is a Wiccan reference.

Womensgrouprituals.com obligingly provided a link to LearnReligion.com’s 12 Fertility Deities. Thus the ubiquitous “12 Fertility Deities” appear three times in the Top Ten of the Duck Duck Go search.

As someone who had been celebrating Bealtaine in a number of different contexts, I felt like I was looking at a very different holiday than the one I’d come to understand. Yes, there are accurate accounts of Pagan practice from Celtic cultures to found on the Internet. But with search results like these floating to the top, it becomes difficult to find them. It was very clear to me that the largest, most well-funded, and most popular websites were taking the lead in defining Celtic practice and Celtic culture for the masses..

Suddenly, I began to understand cultural appropriation from an indigenous person’s point of view better than I had before. What I was experiencing was not the same thing as the cultural appropriation indigenous people from the Americas have been experiencing. But I could see the parallels.

Let’s be clear here. Bealtaine is not Wiccan. It is a Irish and Scottish holiday that Wiccans celebrate. They are free to do so. But failure to make that distinction promotes erasure of these cultures.

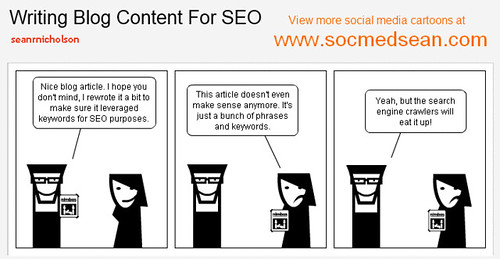

The rise of the internet content farms

Who gets to define Pagan practice from Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, Wales, Cornwall and Breton? What happens to these practices when practitioners who don’t respect these practices dominate the airwaves and define our holidays for us?

More and more people have observed that Google no longer gives you the results you are looking for. This is because entire industries have come into being to game the Google search engine. They do this to put their clients’ websites first on search results. Duck Duck Go operates the same way Google does except it doesn’t store memories of old searches in order to give you results. Basically, you have to have lots of money or lots and lots and lots of free time for people to find your website unless they have your URL.

Learn Religions, Exemplore, and other similar websites have lots of money to spend, so they will be first in line when it comes to pushing their content. Learn Religions, for example, is part of the Dotdash Meredith media company. This big conglomerate operates brands such as Verywell, People, ThoughtCo, Liquor.com and others. You can read their Wikipedia entry to observe how many acquisitions were involved in building this giant media empire. Learn Religions claims to practices the highest levels of accuracy and ethics in journalism. But, well, their actions speak for themselves. Exemplore is owned by another large media company called The Arena Group. This media company describes themselves as being “where the action is.”

Witchesofthecraft.com operates on donations. They seem to have gotten their prominent listing on search engines from posting on a daily basis for many years. Search engines like this. But quantity doesn’t always equal quality. They promote the Celtic Tree Calendar whose historical existence has been debunked as having been invented by the English author Robert Graves.

Implications for Pagan practice

As I’ve said several times before in this article, neither Celtic Pagan practice nor the celebration of Imbolc, Bealtaine, Lughnasadh, or Samhain are closed practices.

But knowing who your ancestors are doesn’t make you one of them. For this reason, I don’t refer to myself as Scottish despite being descended from members of at least three Scottish clans spanning both sides of my family. I don’t even refer to myself as Scottish-American, as I am at least eight generations removed from Scotland.

The cultures of those of us in North America, Australia, New Zealand, etc. evolved in their own directions. The cultures that our emigrant ancestors left behind also continued and evolved after their emigration. There becomes a point where we can recognize our commonalities but understand that we aren’t the same, and therefore, we can’t speak for them . A Scottish writer’s visit to the Scotsfestival event in California had him thinking at one point, “I begin to suspect that that our American cousins don’t love Scotland at all, but simply Braveheart and Outlander.” Though there were other parts of the festival he enjoyed. He acknowledged that there were some things at the festival that the Americans nailed correctly, albeit sometimes by accident.

There was never one single correct way to celebrate Bealtaine. Its celebration evolved over the centuries depending on history and location. But, it needs to be pointed out that there also has been no other time in history where long-suppressed traditions have been picked up by other people not fully understanding the history of the tradition–and then amplify distortions of that knowledge to audiences as large as what we see today on the Internet. Doing research on some of these websites really has helped me realize that the Internet has been both a blessing and a curse for the Pagan community. Pagans that publish need to be held accountable for the accuracy of what they publish.

You may be doing no harm if you are a solitaire Pagan celebrating a distorted form of Bealtaine in the privacy of your own home. (Though some would argue that at least some Celtic ancestor spirits may have quite a different opinion about this). But if you start celebrating these and/or sharing these traditions publicly, it is incumbent on you to be accurate about what is authentic about the tradition and what isn’t. That way, people from the culture from which the tradition originated can more easily reconnect with the tradition as it was.

Imagine what it would be like for people of Mexican heritage if the only Mexican food available was Taco Bell. I actually like Taco Bell’s “Crunchwrap” and have it fairly frequently when I’m on the road. But it pales in comparison with restaurants serving authentic versions of Mexican cuisine, which was developed and perfected over decades and centuries. Now imagine how Mexican-Americans would feel if the only “Mexican food” they can eat is Taco Bell.

Authentic Mexican food is in no danger of disappearing, but to many people, it feels like authentic yoga is nowhere to be found. Indians in the West report experiencing this distortion and lack of access to authentic practice on a day-to-day basis. Yoga is a 2,500 year-old practice.

I can’t speak to the intentions of the Wiccans who first started promoting the Wicca versions of Imbolc, “Beltane,” Lughnasadh and Samhain. But since then, however, more and more research has given us a better picture of the indigenous cultures and Pagan practices of Britain and Ireland. The three links in this paragraph are good places to start to understand Celtic Pagan practice in its original context.

As an eco-Pagan drawn to Paganism because of the novel crisis the Earth faces in the 21st century, I can’t pretend that I have the same intentions as my ancestors. The biggest concerns I have today would probably be unfamiliar and perhaps strange to any ancestor I may have who practiced what many today refer to today as “Celtic Paganism.” Many would share my reverence for the Earth but not necessarily understand the modern context of it.

But part and parcel of respecting the Earth is respecting the native flora and fauna who were here before me. It is incumbent on me as an Earth-oriented Pagan to do my best to help repair the damage that modern humans have done to the ecosystem. We need to help the flora and fauna struggling to survive begin to thrive again. We do so not only because we appreciate the native flora and fauna, but their preservation is also inherent to our own preservation.

Pagans need to regard the rich interdependent tapestry of cultures in this world in the same way.

5 thoughts on “Celtic erasure and how my fellow Pagans often unwittingly contribute to it”